This factsheet contains information to help you understand the law around non-violent direct action (NVDA) on Commonwealth land (or “National Land”) in the ACT. NVDA includes demonstrations, peaceful protests, strikes, occupations or marches that people use to effect change.

Note that this factsheet only discusses non-violent direct action and does not generally cover actions which involve harming property or people.

1. Where is your action happening?

In the ACT, there are multiple types of land, with differing authorities:

| Type of land | Relevant Authority |

| Territory Land | ACT Government |

| Commonwealth/National land | National Capital Authority (NCA) |

| The Parliamentary Precincts | President of the Senate and Speaker of the House of Representatives (called Presiding Officers) |

The law is different depending on whether your protest is on ACT land, Commonwealth land or in the Parliamentary Precincts. This factsheet discusses protests on Commonwealth land and in Parliamentary Precincts only.

If you are planning a protest on ACT land, please see our specific factsheets on NVDA on ACT land.

Is it Commonwealth land?

For a map of Commonwealth land in the ACT (specifically, designated land), see the maroon sections of the map here. The National Capital Authority have produced a publication called “The Right to Protest Guidelines” that also contains a map (page 2) setting out Commonwealth Land in the area in or around Parliament House, and the relevant authorities you need to contact to use land for events (page 10).

Is it Parliament House or the Parliamentary Precincts?

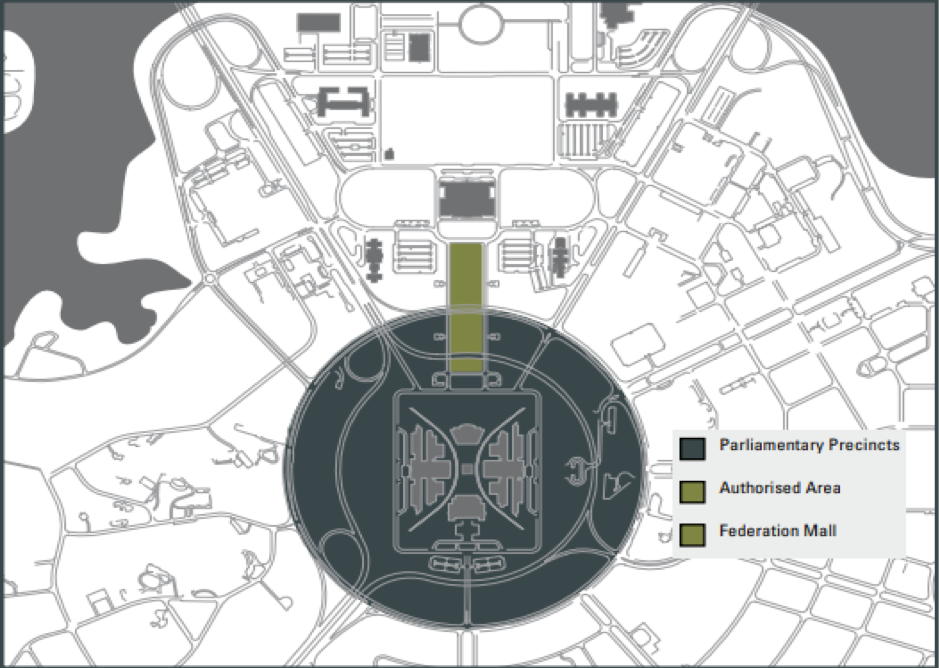

Special laws apply if you conduct a protest within the Parliamentary Precincts. The Parliamentary Precincts are the immediate surrounds of Parliament House (see Map 1). They are managed by the Presiding Officers (section 6(1) of the Parliamentary Precincts Act 1988 (Cth) or PP Act 1988), meaning the President of the Senate or the Speaker of the House of Representatives (section 3 of the PP Act 1988). Federal and ACT criminal laws both apply within the Parliamentary Precincts (section 15 of the Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 (Cth)).

Source: National Capital Authority Right to Protest Guidelines

The Presiding Officers (and by agreement police and protective service officers, discussed below) hold powers for the maintenance of order within the Parliamentary Precincts including:

- Removing or taking into custody any person disturbing the operation of a Chamber of Parliament (except an MP) (Standing Order 96);

- Banning a person who is considered a threat to Parliament from the precinct for a period of time (section 6(2) of the PP Act 1988 (Cth)).

Note that you may be asked to leave galleries in Parliament if your clothing contains printed slogans or is designed to draw attention (House of Representatives Practice).

Although the responsibility for security within the Parliamentary Precincts is vested in the Presiding Officers, security is maintained by the AFP and parliamentary security staff. The AFP in the parliamentary precinct consists of special protective service officers who have special police powers for protective service offences, outlined below.

Case study 1: Protest in Parliament House Foyer

A group of activists held a demonstration in the foyer of Parliament House in late 2018. They were removed from the foyer and given a direction to leave the Parliamentary Precincts under section 6(2) of the Parliamentary Precincts Act 1988 (Cth). They were banned from entering the parliamentary precincts for 9 months.

When may a protest in Parliament House constitute an offence?

Disturbing a chamber of Parliament House is not a criminal offence in itself. However, the disturbance may attract related charges (see Case Study 3 below). In the past, people have been removed for standing up, interjecting, applauding, holding up signs or placards, dropping or throwing objects into the Chamber, chaining or gluing themselves to railings and jumping onto the floor of the Chamber.

Case study 2: Intentional damage to Commonwealth Property

In 2016, seven activists super glued themselves to the railing of the public gallery. They were charged with “intentionally damaging Commonwealth property” under section 132.8A Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth). On the facts, the jury found the group’s conduct did not amount to intentional damage of Commonwealth property.

The NCA’s The Right to Protest Guidelines contains a set of guidelines for protests and demonstrations in the Parliamentary Precincts, Federation Mall and Adjacent Areas (see page 8). Whilst we have included some general information about Parliament House and the Parliamentary Precincts below, the law around Parliament and the Parliamentary Precincts is complicated, and you should seek legal advice if you are planning a protest in this area.

2. Who do I need to notify if I am planning a protest on Commonwealth Land?

Generally, you do not require formal approval to conduct a protest or demonstration within the Australian Capital Territory. However, there are some circumstances when approval is required. “Works” within Designated Areas (including the parliamentary zone between parliament house and Lake Burley Griffin) require approval by the NCA. “Works” includes the erection, alteration or demolition of structures, landscaping, tree felling and excavations (section 4 of the Australian Capital Territory (Planning and Land Management) Act 1988). This approval is to be sought through the NCA’s Works Approval application process.

In the Parliamentary Precincts, protests will generally be permitted in the Authorised Assembly Area (AAA) (Map 1) (see the section 19, Department of Parliamentary Services, Operating Policies and Procedures No. 16 – Protests and other assemblies in the Parliamentary precincts, or OPP 16). However, before a protest takes place an Authorisation to use Parliamentary Precincts – Authorised Assembly Area application form must be completed. Outside the AAA, protests will generally not be permitted (section 19, OPP 16). However, the Presiding Officers possess a broad discretionary power to approve or disapprove any protest taking place within the precinct (section 12, OPP 16). A protest may be exempt from the Authorised Assembly Area restriction by approval of the Presiding officers (section 20(b), OPP 16). For more information and the application form to use the Authorised Assembly area, you can contact the Department of Parliamentary Services ((02) 6277 5999).

3. Protective Service Offences

Protests on Commonwealth land in the ACT may attract “protective service offences”. Protective service offences are offences in relation to a person, place or thing in respect of which the Australian Federal Police are conducting a protective function (section 4 of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979(Cth)). Relevant protective service offences include trespassing on Commonwealth land as well as public order offences within the Public Order (Protection of Persons and Property) Act.

Penalty Units

| For the following offences: Strict liability means that there are no fault elements for any of the physical elements of the offence, and the defence of mistake is available. Absolute liability means that there are no fault elements for any of the physical elements of the office and the defence of mistake is unavailable. “Fault elements” essentially looks at your state of mind when conducting an offence, such as intention, knowledge, recklessness or negligence. |

There is a maximum penalty which may be imposed if you are found guilty of an offence. This may be expressed as a period of imprisonment or as a number of “penalty units” (or both). A penalty unit is the base unit used to calculate the maximum fine which may be imposed for commission of a particular offence. At the time of writing, the value of a penalty unit is $210 under section 4AA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)).

Trespassing on Commonwealth land

Trespass is unlawfully entering someone’s land. Trespass can be a criminal offence, which means you can be arrested and charged with an offence if you are accused of trespass.

Protestors on Commonwealth land should be aware of the following trespassing offences:

- Trespass on Commonwealth premises (section 12(1) Public Order (Protection of Persons and Property) Act 1971, or PO(PPP) Act and section 89 Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)). This is an absolute liability offence with a maximum penalty of 10 penalty units.

- Behave in an offensive or disorderly manner while trespassing on Commonwealth premises (section 12(2)(b) of the PO(PPP) Act). This is also an absolute liability offence and attracts a penalty of 20 penalty units;

- Refuse or neglect to leave Commonwealth premises following an order to leave by a constable, protective service officer, or by a person with Ministerial authority (section 12(2)(c) of the PO(PPP) Act). This is an absolute liability offence incurring a maximum 20 penalty units.

Case study 3: Bloomfield v Brown [2003] ACTSC 43

The appellant was involved in a protest action near the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, on what is now Commonwealth Place. The action involved the lighting and maintaining of a fire. He refused to leave the site when instructed to by a police officer. He was charged under section 12(2)(c) of the Public Order (Protection of Persons and Property) Act 1971 (Cth) and fined $500, which was upheld (affirmed) on appeal.

Offences involving an assembly

An assembly is a group of three or more people that have come together for a common purpose (section 4 of the PO(PPP) Act). Being part of an assembly may be considered an offence when:

- The assembly gives rise to a reasonable apprehension that the assembly will involve unlawful physical violence to persons or unlawful damage to property (section 6 of the PO(PPP Act)). This is an absolute liability offence with a maximum penalty of 20 penalty units.

- The assembly involves 12 people or more, and following a reasonable apprehension that the assembly with be carried on in a manner involving unlawful physical violence or unlawful damage to property, you are given a direction to disperse but the assembly continues for longer than 15 minutes (section 8 of the PO(PPP Act). This is a strict liability offence unless there is reasonable excuse and may incur imprisonment for up to 6 months.

Obstruction

An obstruction occurs when a person obstructs, or contributes to an obstruction of, other persons from exercising or enjoying their lawful rights in a manner that is unreasonable (section 4 of the PO(PPP) Act). Whether an obstruction is unreasonable is determined in relation to the surrounding circumstances, including the place, time, nature and duration of the obstruction (section 4 of the PO(PPP) Act). Such lawful rights include the right of passage along a public street.

As a result, a protest may give rise to an offence when:

- The passage of persons or vehicles into, out of, or on Commonwealth premises is obstructed (section 12(2)(a) of the PO(PPP) Act). This is an absolute liability offence attracting a maximum penalty of 20 penalty units.

- An assembly forms an unreasonable obstruction (section 9(1) of the PO(PPP) Act). This is also an absolute liability with a maximum penalty of 20 penalty units.

- A Public Official of the Commonwealth in the performance of their functions is obstructed, hindered, intimidated or resisted (section 149.1(1)) Criminal Code Act 1995). It is not necessary for the prosecution to prove the defendant knew the official was a Commonwealth public official, or that the functions they were performing were functions as a Commonwealth public official (section 149.1(2)) Criminal Code Act 1995). This offence carries a maximum penalty of two years in prison.

Offensive Behaviour

An increasingly relevant feature of protests, both in the ACT and elsewhere, is the use of confronting imagery or behaviour. Section 392 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT) provides that

A person shall not in, near, or within the view or hearing of a person in, a public place behave in a riotous, indecent, offensive or insulting manner.

The maximum penalty for this offence is 20 penalty units.

4. Other Offences

Note that the Road Transport (Road Rules) Regulation 2017 (ACT) outlines laws and offences relating to the use of roads (including obstruction) by pedestrians. This involves the general crossing of roads and causing a traffic hazard or obstruction. Protesters should be aware of the following road-related offences:

- Staying on a road longer than necessary to cross the road safely (r 230(1)). The maximum penalty for this offence is 20 penalty units;

- Causing a traffic hazard by moving into the path of a driver (r 236(1)). The maximum penalty for this offence is 20 penalty units;

- Unreasonably obstructing the path of any driver or pedestrian (r 236(2)). The maximum penalty for this offence is 20 penalty units.

- Standing or moving on to a designated intersection, and engaging in certain conduct including displaying an advertisement: r 236(4A)). A ‘designated intersection’ is at, or within 50m of:

- Northbourne Avenue with Barry Drive and Cooyong Street;

- Northbourne Avenue with MacArthur Avenue and Wakefield Avenue;

- Northbourne Avenue with Mouat Street and Antill Street;

- Northbourne Avenue with Barton Highway and Federal Highway; and

- Federal Highway with Flemington Road.

5. Police powers and interactions

Providing personal details

If a police officer has reason to believe that:

- an offence has been or may have been committed; and

- believes on reasonable grounds that you may be able to assist in inquiries in relation to that offence; and

- your name or address (or both) is unknown to the officer.

The police officer may request that you to provide your name or address, as long as they inform you of the reason for the request (section 3V Crimes Act 1914 (Cth); section 211(1) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT)). It is an offence to refuse to provide your name and address or to give a false name and address. The maximum penalty is $500 under ACT law (Crimes Act 1900(ACT) s 211(2)), or 5 penalty units under section 3V(2) of the Commonwealth Crimes Act 1914.

If a police officer requests your name and address, you can ask the police officer to provide you with:

- his or her name or the address of his or her place of duty; or

- his or her name and that address; or

- if he or she is not in uniform and it is practicable for the constable to provide the evidence that he or she is a constable.

The police officer is bound to comply with the request truthfully (see section 3V(3) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) and section 211(3) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT).

Providing personal details – protective service offences

As mentioned above, there are special police powers for protective service offences. Special police powers apply to a designated person. A designated person is a member or special member of the AFP or protective service officer (section 14H of the AFP Act).

Under section 14I(1) of the AFP Act, if a designated person suspects on reasonable grounds that a person may have just committed, may be committing, or may be about to commit, a protective service offence somewhere the Australian Federal Police is performing protective service functions, the designated person may request the person provide:

- their name; and

- residential address; and

- their reason for being in the place, or in the vicinity of the place, person or thing, in respect of which the AFP is performing protective service functions; and

- evidence of the person’s identity.

If the suspect fails to comply with such a request, or do so falsely, they face a more severe penalty of 20 penalty units (see section 14I(2) of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth). However, section 14I(2) does not apply if you have a reasonable excuse (see section 14I(3)).

Directions to move on

As referred to in the sections above on trespass and assembly, it is an offence to refuse to leave Commonwealth premises if directed. See above sections on “Trespass” and “Assembly”.

If you do organise an action, you may decide to have people fulfil the following roles to help your interactions with police go smoothly:

- “Police Liaison”: The role of the police liaison is to communicate between activists and police.

- “Legal Observers”: The purpose of legal observers is to monitor, record, and report on any unlawful or improper behaviour including noting actions, the approximate times and witnesses present.

There are several resources available which discuss these roles and the support you can receive when organising a protest. Please see CounterAct (https://counteract.org.au) for more information.

6. Arrest

Who can arrest me?

Police and protective service officers can make arrests in relation to protests on Commonwealth land (see section 14A of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (Cth). In addition, a person who is not a police officer may arrest another person without a warrant. To do so, the person making the arrest must believe on reasonable grounds that the alleged offender is in the process of committing an offence, or has just done so. As soon as practicable after the arrest it must be arranged for the arrested person and any property found on them be delivered into the custody of a police officer (see section 3z of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth); section 218 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT)).

When can the police arrest me and why?

Police arrest without a warrant

At a non-violent direct action, you are more likely to be arrested without a warrant than with a warrant.

A police officer may arrest you without a warrant if the police officer suspects on reasonable grounds that you have committed or are committing an offence and that if they did not arrest you and instead gave you a summons to attend court, one or more of the following purposes might not be achieved (section 3W of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth); section 212 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT)):

- ensuring you appear before a court;

- preventing the continuation of the offence or further offences being committed;

- preventing the concealment, loss or destruction of evidence;

- preventing harassment of, or interference with, potential witnesses;

- preventing the fabrication of evidence;

- preserving your safety or welfare.

This is also similar to the powers of protective service officers with respect to protective service offences (section 14A of the AFP Act).

Police arrest with a warrant

An arrest warrant is a document telling police officers to arrest a person and bring them before a court. A person arrested on a warrant must be brought before a court as soon as is reasonably practical.

What do the police need to do to arrest me?

The police need to tell you that they intend to arrest you. This may involve, for example, saying ‘I arrest you’ or ‘you are under arrest’. There are no particular words that the police officer needs to say to the alleged offender, as long as they understand that they are being arrested.

The police need to show that there has been a sufficient act of arrest or submission. Again, this is so the alleged offender understands they are being arrested. For example, an act of arrest could be touching the alleged offender on the shoulder or arm. A sufficient act of submission could be the person being arrested offering the police officer to place them in handcuffs or stating ‘you have caught me fair and square’.

The arrested person is entitled to know the charge or on suspicion of what offence they are being arrested. However, no entitlement exists if you know the general nature of the alleged offence or if you make it impracticable for the police officer to inform you, for example, by attacking the officer or running away (see section 3ZD of the Crimes Act (1914) (Cth) and section 222(3)(a) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT)).

A person shall not, in the course of arresting another person for an offence, use more force, or subject the other person to greater indignity, than is necessary and reasonable to make the arrest or to prevent the escape of the other person after the arrest (see section 3ZC(1) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) or section 221(1) of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT)).

What should I do if I am arrested?

You can ask “am I under arrest?” and “what for?”. In most cases, it is necessary for police to inform you of the reason for the arrest.

In general, aside from providing your correct name and address, you should not answer questions asked by police. Responses that you provide to questions asked by the police can be used as evidence. You should always get legal advice before being questioned by Police.

Resisting, hindering and obstructing arrest

You may be charged with resisting arrest if you try to stop a police officer from arresting you. This falls under the obstruction in s 149.1 of the Criminal Code 1995 (Cth) previously discussed and sections 361 and 363 of the Criminal Code 2002 (ACT).

Even if you think that you are innocent of any offence or that there is no proper reason for arresting you it is wise to submit to an arrest. By resisting arrest you are committing an offence that you may be charged with, even if the police do not charge you with any other offence.

7. Police powers following arrest

Search powers

Following arrest, a police officer may search you. For a detailed description of search powers, refer to the ACT Law Handbook (http://austlii.community/foswiki/ACTLawHbk/PoliceStopAndSearchPowers).

Having searched the person under arrest, a police officer may seize any items found that may constitute evidential material or a seizable item. A police officer who seizes items is required to make a record of the items seized and give them to the officer in charge of the police station for safekeeping (section 229 of the Crimes Act 1900 (ACT).

How long can I be detained by police?

Ordinarily, a person being investigated may not be detained without charge for longer than 4 hours, or in the case of a child or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person, 2 hours (section 23C(4) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)). Importantly, different provisions apply to offences classified as terrorism offences. The detainment period may be properly suspended by police in certain circumstances (e.g. during a period when a person under arrest is contacting a lawyer or friend). In the case of a serious offence (punishable by more than 12 months imprisonment and not being a terrorism offence) a magistrate may extend the investigation period (section 23DA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)).

Obligations of investigating police

Police must treat a person under arrest with humanity and respect for human dignity. Additionally, an arrested person must not be subjected to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment (see section 23Q of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) and section 19 of the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT)). An arrested person has the right to:

- A caution: Before a police officer starts questioning, the police officer must caution the alleged offender that they do not have to say or do anything, but that anything they do say or do may be used in evidence (see section 23F of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth));

- To communicate with friend, relative or lawyer: Before questioning, you must be informed that you may communicate or attempt to communicate with a friend, a relative, and a lawyer of your choice or attempt to arrange for a lawyer to be present during questioning. Questioning must be deferred for a reasonable time to allow these to occur and you must be provided with reasonable facilities (see section 23G of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth));

- Legal advice: If a lawyer attends, you must be allowed to consult with the lawyer in private and in reasonable facilities and the lawyer must be allowed to be present during the questioning and to give advice to the person (see section 23G(3) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)).

Think about your legal representation in advance: It is often a good idea to find a lawyer to be “on-call” for your group. Some activists write the phone number of a lawyer on call on their body so that if there is a problem, then they have someone to call.

Note that there are specific obligations on investigating officials for investigations in the following circumstances:

- For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (see section 23H of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth));

- For people under 18 years of age (see section 23K(1) of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth));

- People unable to communicate fluently because of inadequate knowledge of the English language or a physical disability (see section 23N of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth));

- People who are not Australian Citizens (see section 23P of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth)).

What happens after I am arrested?

For an explanation of criminal process, including bail and sentencing, please refer to the ACT Law Handbook (http://austlii.community/foswiki/ACTLawHbk/PoliceArrest).

8. How do I make a complaint about the police?

You can make a complaint to the AFP by:

- Filling in the online complaints form

(https://www.afp.gov.au/contact-us/feedback-and-complaints)

- Attending or telephoning any AFP police station or office, or

- Contacting AFP Professional Standards: (02) 6131 6789.

If you remain dissatisfied after making a complaint to the AFP, you can make an online complaint to the ACT Ombudsman (https://www.ombudsman.act.gov.au/making-a-complaint/common-complaints/act-policing).

9. Common questions

Will I have a criminal record and what are the impacts?

If a court finds that you are guilty of an offence, this may go on your criminal record. Courts have the discretion to give you a penalty without recording a conviction. This depends on the circumstances and the nature of the charge. The impacts of a criminal record will depend on your circumstances. The impacts of a criminal record will depend on your circumstances.

A criminal record may impact on your ability to work, travel and obtain certain licences. The nature of your criminal conviction is relevant – for example, a trespass charge is less likely to impact on a working with vulnerable people card. However, some employers ask for a criminal record check, as do organisations such as embassies and those that issues licences. Whether or not you have a criminal record may impact on your chances of employment or your ability to travel to certain countries. You should assess our own particular risks, given your personal circumstances.

If your action is within the Parliamentary Precinct, you should also consider how a ban from the area may affect you, for example, if your employment requires that you go there.

Who can see my criminal record?

Information about your criminal record is classified as ‘sensitive information’ under section 6 of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) which must not be collected by an agency or organisation unless it is ‘reasonably necessary’ for the entity’s functions (see Schedule 1, section 3.3 of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)).

Will I be able to get a Working with Vulnerable People Check?

This is a State or Territory based scheme so your eligibility may vary if you are outside the ACT.If you have a criminal record, you may still be able to get a working with vulnerable people card. The Commissioner for Fair Trading will be able to view your record and assess it in deciding your application. If you apply for a card, you must consent to the Commissioner checking your criminal history and non-conviction information, including any convictions, findings of guilt, and spent convictions (see sections 18, 24 and 25 of the Working with Vulnerable People (Background Checking) Act 2011 (ACT)).

Will my criminal record be around forever?

In the ACT, the Spent Convictions Act 2000 allows you to stop disclosing certain State and Federal criminal convictions. This is usually 10 consecutive crime-free years, or five if you were a child when the offence was committed (section 13 of the Spent Convictions Act 2000). Whether your conviction can be spent depends on how serious it was (section 11 of the Spent Convictions Act 2000).

The Commonwealth also has a spent convictions scheme in Part VIIC of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth). The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner has a useful factsheet on this scheme at www.oaic.gov.au/individuals/privacy-fact-sheets/general/privacy-fact-sheet-41-commonwealth-spent-convictions-scheme.

Where can I go for more information?

- Contact the National Capital Authority ((02) 6271 2888, www.nationalcapital.gov.au);

- Contact Legal Aid ACT (1300 654 314, www.legalaidact.org.au);

- Contact the Environmental Defenders Office Sydney office, who run a Citizen Representation Program that may be able to assist ((02) 9262 6989);

- Contact the Environmental Defenders Office Canberra office ((02) 6243 3460).